Interview by Sean Bendon

Video by Sean Bendon

It’s been over a year since I first met Rob and started talking to him about his long and interesting past in skateboarding. It never occurred to me that it would take so much time to make this thing happen but now that it’s all finished I can’t help but feel like there’s still so many things to be said.

Rob has had an impact on your skate life whether you really know it or not. There’s so many things we didn’t get to talk about in this piece and a bunch of his work we never even touched on.

Just a few things to give you an idea:

- He made the original ENJOI umbrella logo.

- He ran a few wheel companies back in the 1990s, including The Wheelie Company and Landspeed wheels.

- Here’s a few skaters that rode for The Wheelie Company: Pat Smith, Brian Seber, Chris Weichert, Donny Barley, Jason Skupackus (rip), Kenny Hughes, Chad Kramer, Mike Maldonado, Jimmy Chung, Kevin Taylor, Brian Gaberman, Bam Margera, Ryan Wilburn, Kerry Getz, John Montesi, Brian Gaberman, Sam Hitz, Brian Howard

- He was behind the making of the first CKY video which came out for Landspeed Wheels and played a part in kick starting the career of Bam Margera, along with many other east coast legends.

- He and friends built the Autumn bowl in Greenpoint back in the early 2000s.

- He moved in with Coan Buddy Nichols and Rick Charnoski, who went on to create Sixstair studios and produce one of the best shows in skating “Loveletters to Skateboarding” with Jeff Grosso.

- He did the art direction for Fruit Of The Vine – Buddy and Rick’s first film while roommates with them.

You’re more than a skate photographer but for the purpose of this interview we’re gonna focus on that. When did you first pick up a camera and what got you into Photography?

Seeing pictures got me interested in it. Skate mags, BMX mags, music mags, all that stuff. My grandmother shot lots of pictures and she had cameras around. She gave me a camera for my birthday, a little 110 point & shoot. When I was older, I got a 35mm camera and took it on a skate trip. My really close friends shot photos and were way more serious and could develop their own film, actually compose skate shots. That got me into it. Then I got into art school and got wide-angle lenses.

How was going to college for photography and printmaking?

They go hand in hand. I mean, there’s a side of printmaking that is not photo-based but I was very interested in the more graphic, mechanical, photo-based screen printing. And the darkroom was right next to the print shop. I could start using the camera more like a tool, versus, a specific art making device. It was like, “oh I need this image to incorporate it into a print I’m working on.” Instead of appropriating an image, I could create one from scratch. And then, manipulate it either in the darkroom or in the print shop, on a computer, bring it all together and make something with it, whether for personal work or a commercial project like a poster or a skateboard graphic.

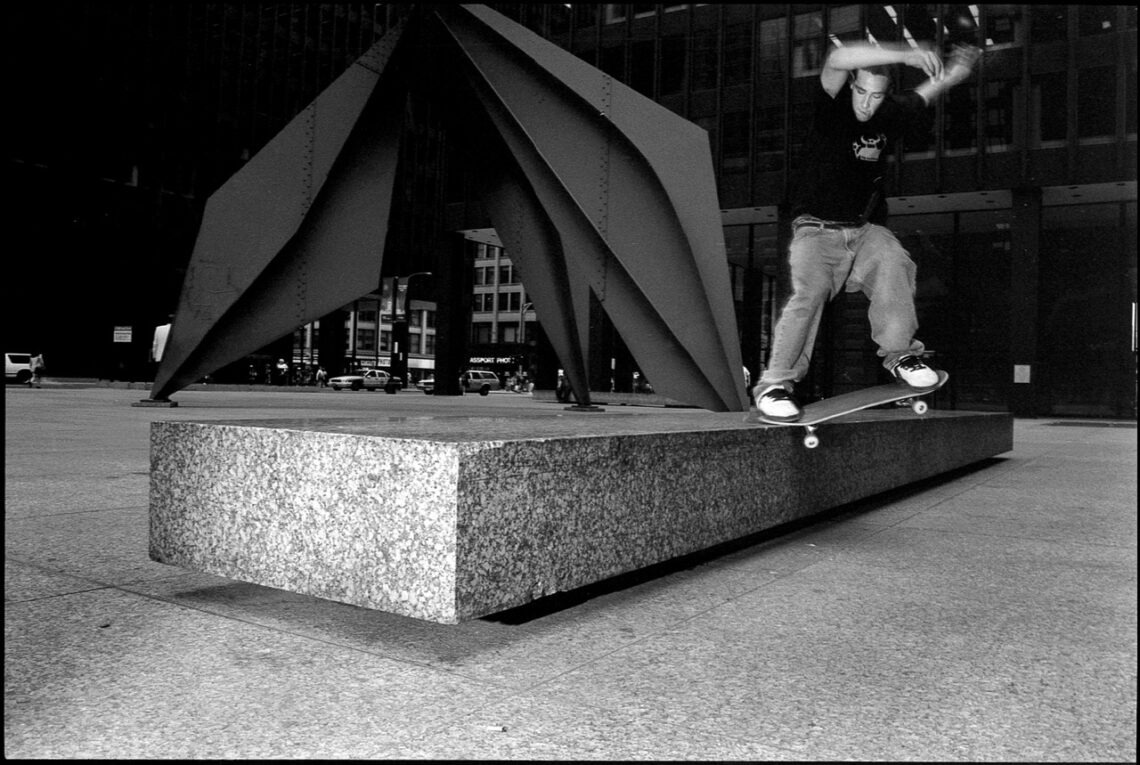

You got a job at Tum Yeto from O (Otis Barthoulameu) and ended up moving out to California. I know that some of the skate graphics you made were from photos that you had shot, specifically the Donny Barley board you showed me with the photo from Nebraska. Can you briefly explain how working for Tum Yeto was and how you incorporated your photography into the job you did there?

Working for Tum Yeto was incredible. It was like a dream come true. Getting a phone call from somebody like O was… First, I thought someone was pranking me. The more we talked, the more I realized it was the real deal. At the time there weren’t a lot of graphic designers that understood the printmaking process and how art was transferred onto a board because boards were silk-screened. They still are, but there is a more indirect process now with heat transfers. The artwork was color separated and printed one color at a time. It’s really difficult when a graphic or an idea comes in as a composite with many colors and gradients and is literally a two-dimensional object, which then has to be taken apart, color separated, and printed while keeping all the integrity of the original piece intact. There’s stuff that just gets lost in translation. I already had a lot of silk-screening experience from school and they saw it and they were like, “hey, we like what you’re doing and you know how to get it done.”

Who were some of your photo influences at the time and who were some of your photo peers at the time?

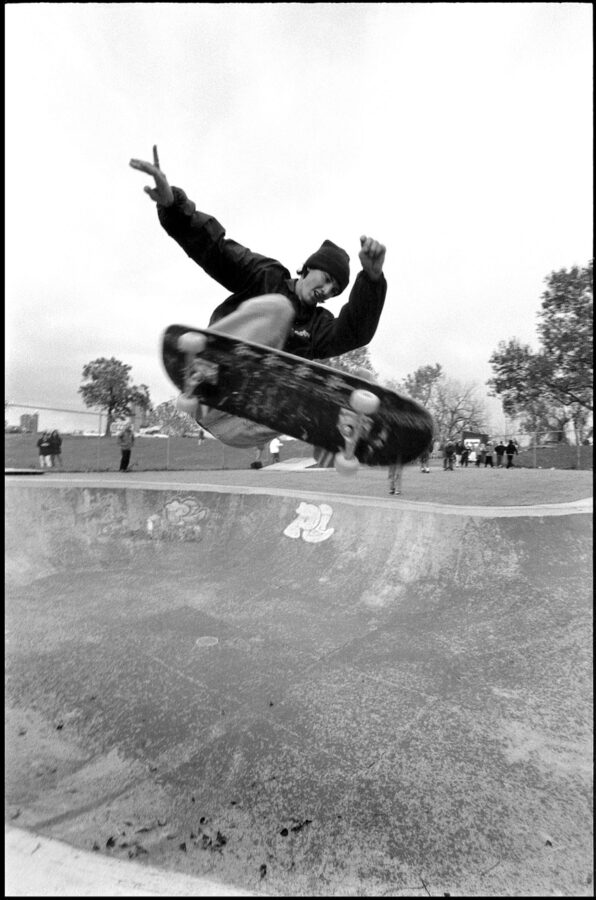

Around that time, influences and peers would be like… hand in hand, as far as skateboarding goes. O (Otis Barthoulameu) 100%. When we connected, he was still shooting photos, but in a much more laidback way. He wasn’t objectively going out and doing it for work. He had become much more immersed in music. But that didn’t keep him from shooting photos. He was probably the biggest influence. Same with Tod Swank. Even though at that time Tod was not shooting photos for a living, he was running a business. But his photography was just bar none. It really, really had an impact. He had a good eye for the person, the trick, the spot. The technical aspects, the exposures, everything about it. It felt like you could just reach into the picture. Tobin Yelland was huge, Lance Dawes. Those guys, they really capture an image that translates everything but it also has this deeper feeling or a mood. They could shoot a very polished photo and then also just go out and document raw stuff. Slice of life. That was important. And music photographers too, there’s a lot. There is a book called Banned in DC by Cynthia Connolly that had a huge impact on me. The book is just really straightforward, black and white, just capturing the bands and people unfiltered. It wasn’t really the camera doing all the work, it was the subjects.

Back in the 90s, you ran a couple of different wheel brands, when you were doing the ads, were you shooting, developing, doing layout? What was your involvement in that process?

A lot of the time it would be another photographer, but there would be times I would find myself using photos I shot too. And that would usually be because there wasn’t anything else I could get in time to meet a deadline. It wasn’t every time but my photos would find their way into the mix. I was pretty critical about it. If it had something to do with a team rider or someone that was going to be in the ad, I definitely wanted them to feel good about it. When I was running Wheelie Co. it was on a shoestring budget. And sometimes those ads would just be made with whatever was sitting on the desk. Sometimes it wouldn’t even be a skate photo.

Do you remember getting your first skate photo published?

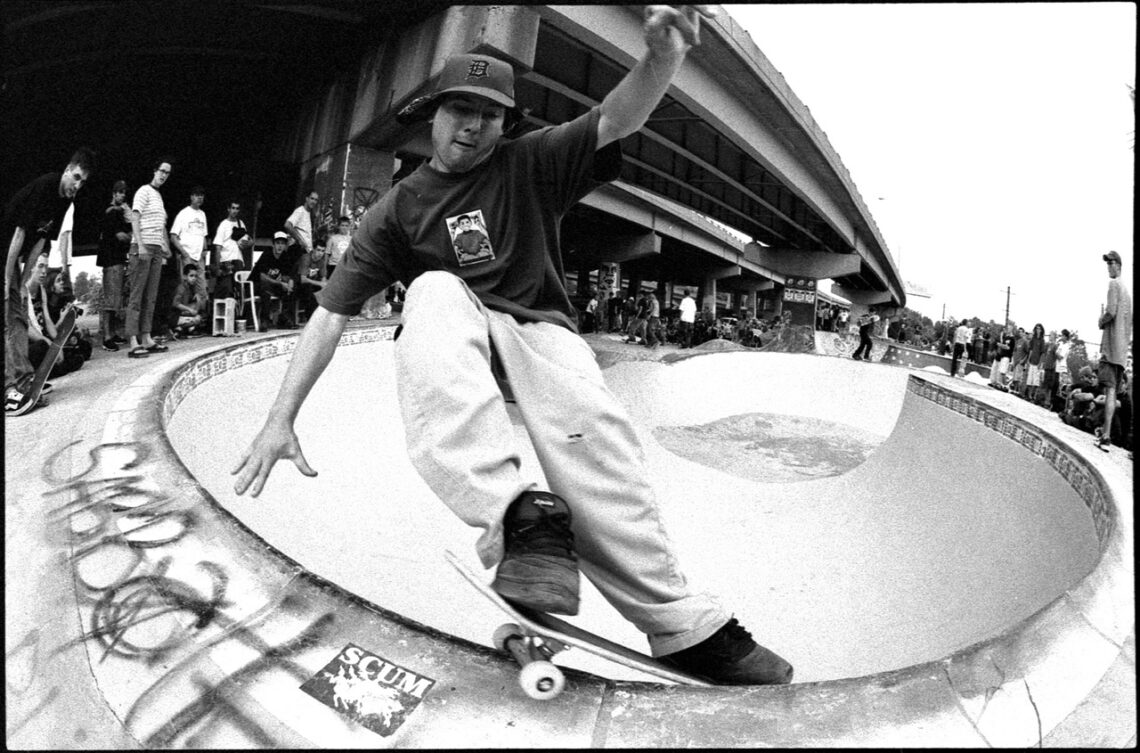

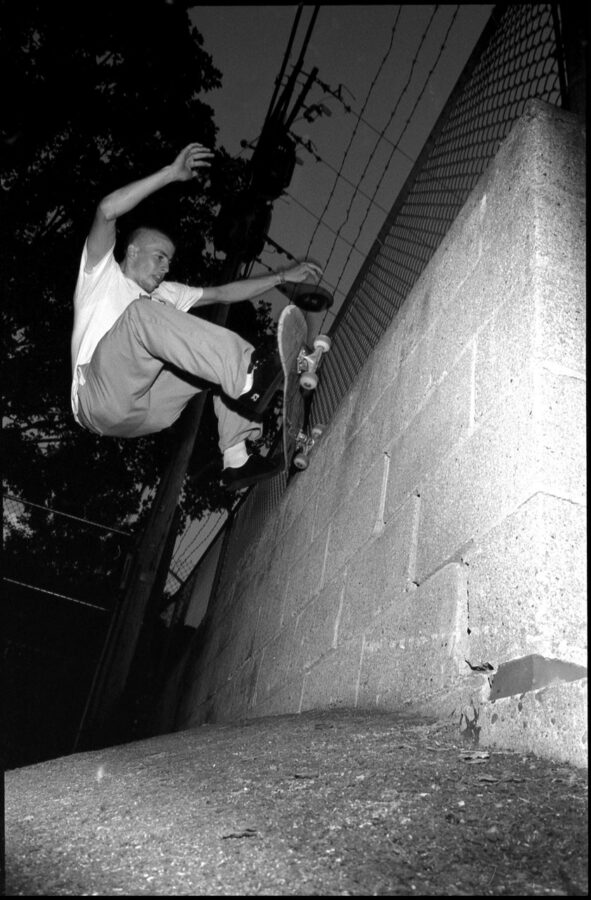

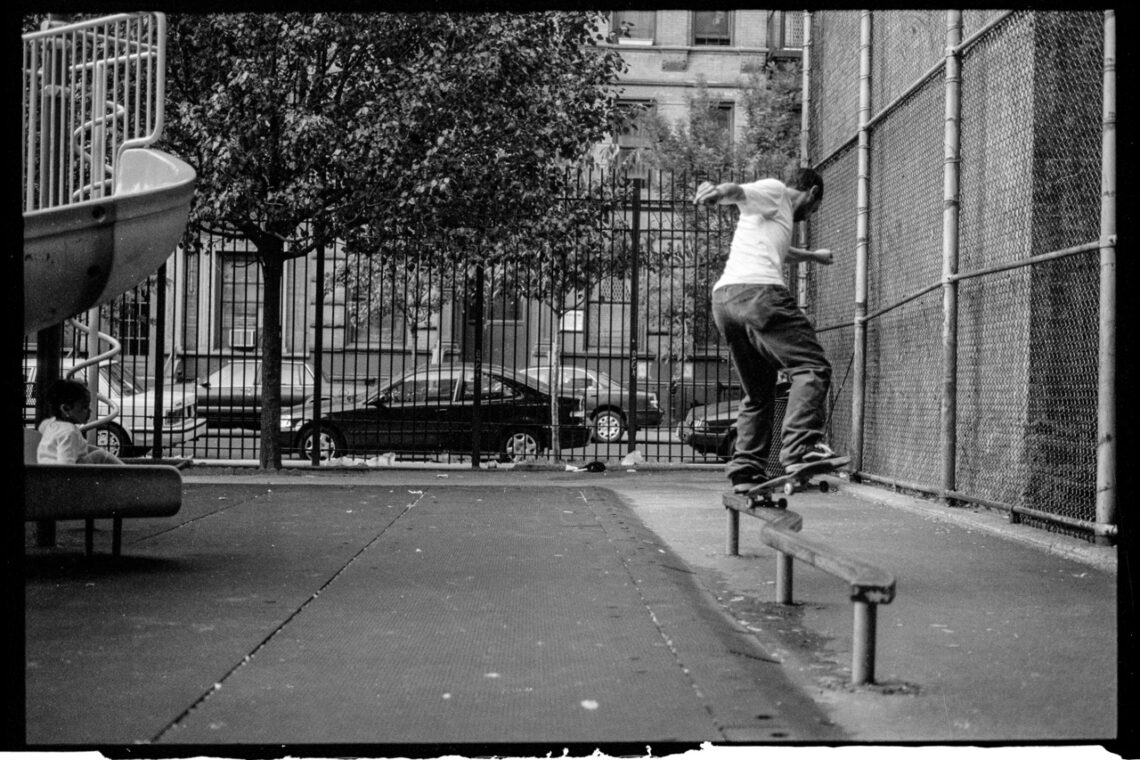

Yeah, it was in a German magazine. It was a photo of Donny Barley ollie up to fs pivot on a wall.

Was there a period in your life where you felt like you were at the peak of your productivity as a photographer? Where you were always shooting, hanging out, always had the camera?

There was a time where the camera was always around but I never felt like I was at any sort of level of comfort. Cause it was always either gear changing or demands were. There’s just a bullet list of things and the list is always changing and reordering. You are always on your toes. And if you’re in a city like New York, the place changes by the minute and there’s always something. There’s just new faces, new people, new environments, new things, new dynamics. Then you compound it with technology and all kinds of other stuff, your age, your energy, and your willingness to go at it by all means necessary. Yeah, you’re never comfortable and you shouldn’t be. If you’re in a creative place and you’re comfortable, you’re not in a creative place. The two do not coexist, because creativity exists in the margins. Out there, it’s not comfortable. If you’re thinking about something creative, it’s something that is pushing the envelope. Otherwise, it’s just status quo.

Can you tell me about SPUNK mag?

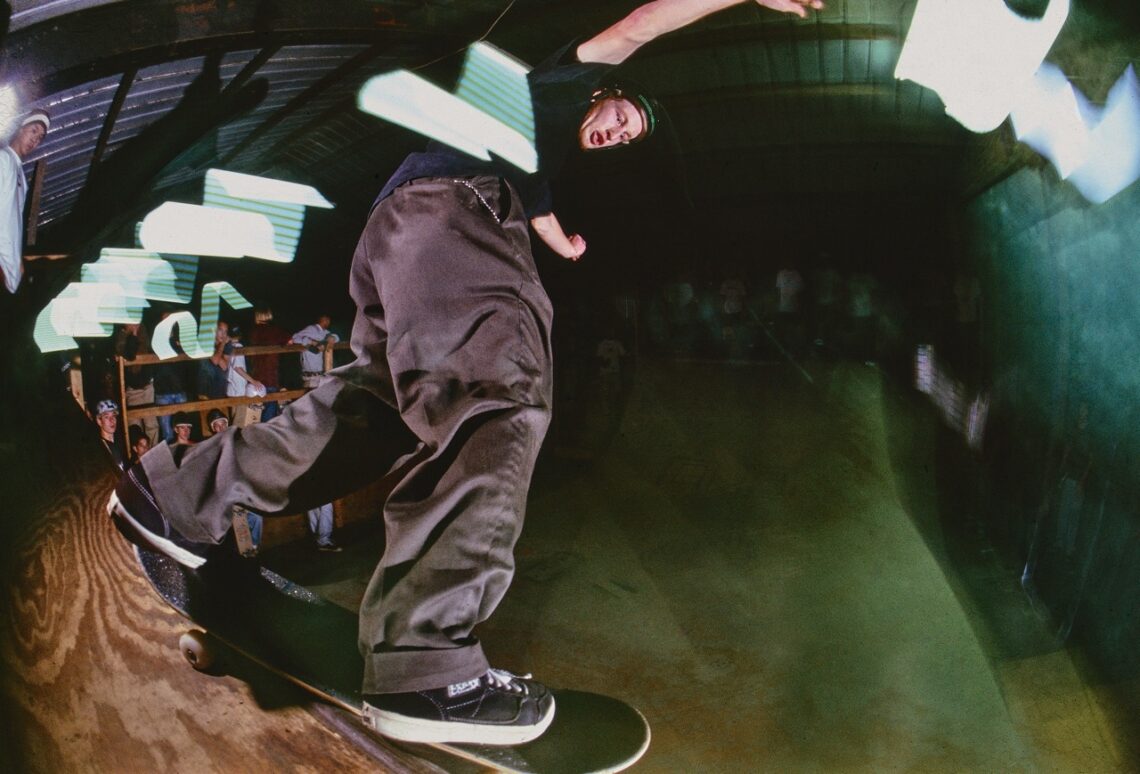

Spunk was a skate zine. First, it was done by my friend Jim Tesnar in the early 80s. Jim was the first person that really had an impact on me in skateboarding. He used to skate this ramp at my friends across the street from my house and I’d go over there after school and skate with them. I was little and they were like college kids. The zine was the first kind of homemade thing I ever got in skating. Spunk became a mail order skate shop, then an actual shop, and then it was a skatepark in the 90’s, and then he made boards. All run by Jim. He still works in the industry. At one point he was like,”let’s make a zine just for fun.” I was down to help. The more we talked about it, we figured it would reach everybody if we just made it online. I knew how to build web stuff out and design it and make it work. We made it a full screen presentation which at the time was not being done. It was in a linear format and paged through from start to finish. It wasn’t like a conventional website with a bunch of options to navigate. It was just pictures and articles that we thought were interesting. There would be totally unknown ams and then a legend like Scott Foss who was pro in the late 70’s early 80’s. It was really fun. Looking back on it there’s a lot of people in those issues that have gone on to do things that were unknown at the time. We did interviews with Nora Vasconcellos and Samarria Brevard before they were known. There was a cover of Jimmy Wilkins when few knew who he was, doing a huge frontside ollie. There was stuff coming in from photographers who were being very generous that were just happy to contribute that weren’t very established photographers and we were giving them a platform to show their work. But then it just got to a point where it was taking a lot of time and there were other things happening in my life that required a lot of attention, work-wise, life-wise, etc. It became hard to find time to do it to the level we wanted.

Did you have photos in Spunk as well? Were you shooting at that point or were you more in an editorial position?

I was contributing photos, but I felt a little weird putting a lot of photos in there. I had plenty to show. But I wanted to just keep more of an equal opportunity. I wanted it to look like, hey, this is a thing we are making for skateboarding. And, you know, there’s a lot of people out there doing stuff and we want to put the stuff we like down the pipes for people to see that we think is good. So many people were being cool sending us photos and interviews to use for free, you know? That takes precedence.

Are you glad you took all these photos now?

Big time. I found something yesterday and I was like “fuck, why didn’t I ever print that frame?” And here I am seeing it now. I just wish I looked at the contact sheet a little closer. But you can look at it, memorize 36 frames and take all the inventory in it, but ten years down the road it’s gonna change. And there’s a photo in there that will mean something completely different in the present than it did then. You know, the money shot is now kinda like, eh, whatever. And then there’s this other one that transcends time. If I went through today and audited everything I shot, and then did it again five years later, I’d have two different results.

Do you remember the last skate photo you shot?

Yes, it was Kevin Maillet doing an ollie over a bar in the neighborhood. Kev rules.

What role does photography play in your life now?

It’s a tool. I use it to catalog my work. I still take pictures of stuff. But I’m not out there always looking and taking pictures of everything I see. I had a hard drive meltdown on me several years ago, and it just pivoted me in a completely different direction. I put all my life and creative energy into a hard drive just to have it die and work lost. There were two books I was working on that are gone – up in thin air. I sent the hard drive to the gnarliest forensic tech place. One of the highest-level tech recovery programs at RIT in Rochester. “We can’t get anything off this thing. It’s toast.” I was transferring all the files off of it when it died, and I lost it. That’s where I was like, I’m just gonna paint now.

What advice would give to someone trying to break into photography?

A photographer asked me that question and I said, “get a day job…” and they got mad. Supplemental income so that you can make your work. You don’t break in. You don’t break into anything. You find your

way. And when you’re finding your way, you’re doing whatever you can to pay for your day shit and your life. The ability to sustain yourself when your art ain’t paying the bills.

What advice do you wish someone had given you earlier on for photography or maybe just in general?

I never got advice for photography because I didn’t seek it in terms of career. I knew the drill. And the drill was send it in and keep shooting. It goes back to patience. Be patient and have other things to carry you through it. Be creative about it and don’t say no. The best advice I got about life and surviving in a creative field was during a time when shit hit the fan. A very good friend of mine, Adam Wallacavage, was like, “right now, I’m just not saying no to anything, and I’m doing whatever I can.” He shoots for fun, it might get published, and he’s happy. But there’s other things occupying his life that are creative and have rewarding results. Don’t say no and do whatever you can to maintain the direction you want to go in and be passionate about it. Be dedicated to it.

Any shout outs?

Zillion. Off the top of my head, thanks Mom, thanks Jim Tesnar day one forward, Spunk was the funnest skatepark scene with the best atmosphere 100% start to finish. Thanks for that phone call Otis B – you are still here on so many levels, especially on all the rad records you made. Thanks Tod Swank, Pete Thompson, Dan Wolfe, Adam Wallacavage, Kelly Ryan, Brian Emig, Doug Thompson, Dane Wilson, Brian Gaberman, Rhino, Randy Janson, Marc Johnson, Greg Witt, Andy Jenkins, Kevin Wilkins, Bobby Puleo, Slap Magazine, Thrasher Magazine, Ryan Henry, Jaime Owens. All the skateboarders and musicians and bands that stoke the fire, inspiring photographers, people who push the envelope, Al and Andy Duvall, Marcus Durant, Steve Albini for showing us what DIY means, Mark Hubbard for showing us what DIY means. Buddy Nichols. Thanks to Rick Charnoski and Evan Becker for giving me a place to live when I moved to the city from California with a camera, skateboard, bicycle, and 90 bucks to my name.