Words and photos by Luke Kim.

p- Olympia

“The skatepark is called Lukaba Hande which loosely translates to “everything will be alright.”

Wonders Around the World is an organization of professional builders that volunteer their time to build skateparks in developing nations. This particular crew can knock out over four parks a year and endlessly give away their knowledge and time for nothing but the love of traveling and spreading skateboarding. Mongu, Zambia would be my fourth build with this crew, and the second completed during the Covid-19 pandemic.

I showed up at the airport four hours before my departure time, but the pandemic-induced complications still made things difficult. The rule to travel to Zambia was one needed a Covid test at most 72 hours before arrival time. With a layover it takes about 50 hours, which means you have to take the Covid test less than one day before your departure. I had taken my test two days before, so due to the time zone change I would not make the cut and was almost not let on the flight. Three and a half hours later, and many emails and phone calls to and from the airport in Zambia, I was allowed on the plane with ten minutes to spare.

The Happy Hippo, the hostel we stayed at once we landed in Lusaka, had an American built pool that hadn’t been filled yet. With a tight and untouched pool, beers, and good company, we met up with half of the crew at the Happy Hippo, and then would travel another thirteen hours to Mongu, in central Zambia.

p- Luke Kim

Although building in developing countries makes things much easier and cheaper permit-wise, there are constantly problems you wouldn’t expect. From keeping in check with the budget to making sure the local relationships with the builders are healthy, there’s a lot that goes into these builds that pushes each one of us to be flexible and roll with the punches. The first couple days people were getting heat exhaustion due to how dry and hot the weather was, so the timing of when to work became a factor. But with the energy and help of the local kids, it was easy to want to get things done and they ended up working just as hard as the builders.

p- Luke Kim

“Hallucinations grew with the sleeplessness, which became increasingly worse.”

Five days of the build had passed and I had been feeling extremely tired. Part of the crew had been feeling sick but I assumed it was just heat exhaustion from the sun. Every time I would lay down for bed my body would heat up to an unbearable temperature. There was a big celebration when many of the French crew members had arrived where we rolled joints, laughed, and shared drinks and conversation, but later that night there was a lingering pain in my throat I hadn’t felt before. I decided to go to bed early but I couldn’t sleep due to the heat. The sleepless nights persisted for another two days and my body kept overheating. I did not have any cold symptoms, just a nasty headache that wouldn’t go away. Within those two days my appetite had subsided and Mateus gave me an at home rapid-Covid test. It showed negative so the next option to check for was Malaria.

By day seven of the build, I couldn’t eat or sleep and my headache had gotten increasingly worse as well. I had gotten a Malaria test at the hospital but the test came back negative. That night I couldn’t sleep again and the pain ended up being so unbearable that I woke up Martin and Mateus, the organizers of Skate World Better. They gave me another rapid test and I ended up testing positive twice that night so I isolated myself in another room. I had no choice but to move into a separate hostel in Mongu, away from the crew and people in general. Hallucinations grew with the sleeplessness, which became increasingly worse. I had full, in-depth conversations each night with my friends in the hostel that were never there, then I started having cough attacks every ten minutes and couldn’t think straight. After five nights like that I started coughing up blood, but it still took me another day to start looking for some sort of better care.

I knew I needed to change something because my body was deteriorating pretty rapidly. I had lost over fifteen pounds and my lips were purple due to lack of oxygen.

The one thing that made me feel better were the friends that came to visit me, but this sickness is highly contagious and would put them at risk as well, so the visits seemed painfully few and far between, obviously for good reason. My friend Chuy ended up having to convince me that going to the hospital was the best bet for me. Though I had accepted the possibility and risk of catching Covid, I wasn’t prepared for how severe the situation could turn. Nobody was sure what hospital would be safe and conducive to my condition. In Zambia, being a tourist makes you stand out and automatically puts a target on your wallet, making the thought of a hospital feel horrifying, especially after seeing the hospital in Mongu. Mateus thought to call the US embassy in Zambia for a recommendation of a hospital for me in the capital, Lusaka.

“Not only was my body deteriorating, but the situation around us seemed to as well.”

On the eighth day, a car was organized to take Chuy, Olympia, and myself on the thirteen hour trek where they would drop me off at the recommended hospital, then continue their journey to drop off skateboards to the small scene in Solweizi, which is six hours north of Lusaka. Not only was my body deteriorating, but the situation around us seemed to as well. The taxi we were in had broken down over three times and on each occasion the driver kept getting out and doing something under the hood. At the time, it seemed like a good idea to take codeine to ease the pain of my chest and help me breathe, but the mixture of Covid fog and being on codeine made it hard to navigate through the scenario and distinguish reality. One of the times the taxi broke down, I got out of the car to see what the driver was doing and to my awe he was cutting up coke bottles to make his own radiator hose. I look down at his DIY radiator hose consisting of plastic chip bags, soda bottles, and rubber bands, to keep his car running for a thirteen hour drive. All of us were so frustrated with the situation that we found another taxi and transferred all of our things without any remorse for not paying. As soon as we sat down in the new taxi I realized I left my phone in the first car but when I turned around, it was gone. On a trip to a developing country, a smart phone can be a crucial lifeline and mine was suddenly traveling far away.

“One of the times the taxi broke down, I got out of the car to see what the driver was doing and to my awe he was cutting up coke bottles to make his own radiator hose.”

We made it to the hospital at 4:30 in the morning, after leaving at 11am the day before, frustrated, tired, and without my insurance information because it was on my phone. The nurses at the hospital were waiting for me to enter. They opened the door in full hazmat suits and the comedown of codeine helped the fluorescent lights thoroughly burn my eyes. I was on day nine of Covid and though I had been getting worse, the PTSD of the hostel had led me to be completely terrified of being in isolation again. The first thing the nurses needed to do was test me for Covid but if I was positive they would isolate me for another 14 days, regardless of whether I tested negative after. It seemed like the white walls were closing in on me and I had my first anxiety attack. I couldn’t breathe to calm myself down, my right lung felt like a deflated balloon and the situation felt unbearable. I ripped off the vitals and ran out of the hospital to catch my friends to tell them I couldn’t stay.

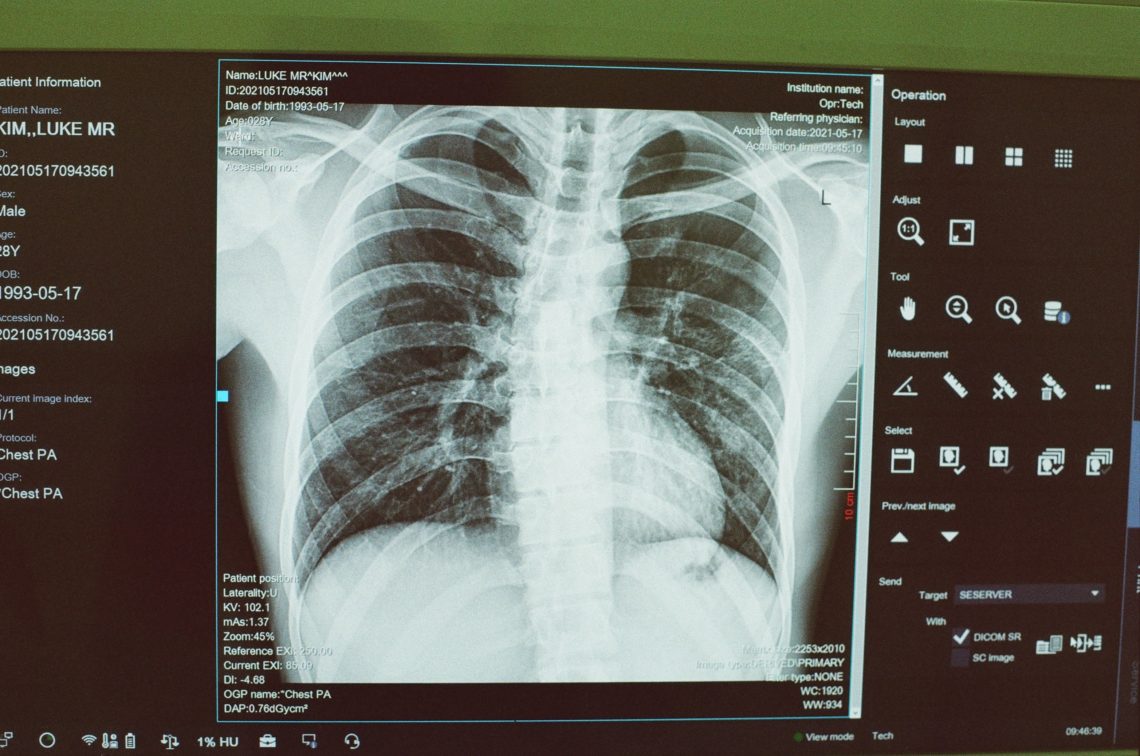

We went back to the good hostel, The Happy Hippo. The fear of going to the hospital had been so great that I had subconsciously convinced myself I was better the next day, though I was probably worse. The local artist Morris had shown us love and helped me get a new phone and recollect all the things I needed to get better in Lusaka. After a couple days of good friends surrounding me, I decided to go to a different hospital I felt more comfortable at. They x-rayed my chest and I had three to four punctures in my lungs, explaining why my right lung felt useless.

“I had less than a one percent chance of getting punctures in my lungs from Covid, and almost fifty percent of these cases lead to death.”

Things finally started getting better from there. They had to keep me for ten days because even though I didn’t have Covid anymore, it had progressed into pneumonia and the infection on my right lung was growing steadily without antibiotics. It turns out I had less than a one percent chance of getting punctures in my lungs from Covid, and almost fifty percent of these cases lead to death. After a few days I immediately started feeling better. We even set up a system to befriend the guards to let me out to get cookies from the store. The security guards were so friendly they ended up cooking inshema (the local carbohydrate) and beans and were happy to talk with me and shoot the shit.

The hospital was a breeze compared to my time in the hostel. I had all the time I needed to myself to set everything straight in my mind and life. Family relationships were mended via communication, finances were set straight, goals for the rest of the year were set in place. Mistakes and issues I’ve made and had in my life were mulled over and accepted. I got out of the hospital and took a bus to Mongu as fast as I could. The dirt that I had seen three weeks prior was an entire skatepark, with everything done except the one last pour of flat.

“I helped wheelbarrow and screed the last section and got to celebrate, not only surviving Covid and pneumonia but the first skatepark of Zambia.”

p- Uzi

p- Uzi

p- Uzi

After Mongu, parts of the crew had decided to go visit the rest of the country. We went to Siuma, Victoria Falls, and back up to Lusaka which seemed to be one endless party in which we saw crocodiles as well as baboons.

p- Luke Kim

When our crew made it back to The Happy Hippo, we skated the pool for two days straight and it ended up being the perfect way to end the trip and split ways. The love of the crew and the locals that welcomed me back home to Mongu and Lusaka was intoxicating. The energy and excitement that these skatepark builds can bring to communities are like nothing I’ve ever experienced. The skatepark is called Lukaba Hande which loosely translates to “everything will be alright.” Show love to your friends, family, and fellow skateboarders, and remember, everything in this life is temporary. Lukaba Hande.

You can learn more and support Wonders Around the World by clicking here

Learn more about Lukaba Hande Skatepark by following @weskate_mongu101